Our brains allow us to see things and make sense of what we are doing. They allow us to take action: to move purposefully and do things when we need to or want to. They allow us to hear: to interpret vibrations in the air, to identify where they are coming from, and to identify their likely cause. They do the same for all of our other senses, including the sense receptors we have inside our bodies, which tell us what our muscles and joints are doing. Our brains make it possible for us to locate ourselves in the material world: to receive information from it, and to act within it.

Our brains also allow us to remember things – and in more than one way. They store conscious memories, like PIN numbers and addresses, but they also allow us to remember things that happened in the past, and even allow us to remember to do things in the future (most of the time!).

Our brains allow us to store skills, so that we can perform actions or cognitions smoothly and without consciously thinking about the steps involved; and they store patterns and meanings, so that we can make sense of new things that we encounter. They even allow us to imagine things that might happen in the future – or things that might never happen.

As social animals, it is important that we are able to recognize people, and it is our brains that allow us to recognize faces and bodies, and to distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar individuals. Our brains also make it possible for us to develop the attachments and relationships that are the basics of social living and to communicate with other people, using words, signs or symbols.

At a more abstract level, our brains also make it possible for us to deal with the three Rs’ – reading, writing and arithmetic, each of which involves distinct areas of the brain. But being human is more than just having mental skills of this kind: it is our ability to empathize with others which really makes us human, and our brains also provide us with the mechanisms for self-knowledge, identification and empathy.

We have emotions, too, and these are only possible because of how our brains have evolved. We feel anger, fear, happiness and disgust, we feel pleasure and pain, and we respond to rewards. We have times when we are alert and agitated, times when we are relaxed or experiencing states like mindfulness, and times when we are asleep. These states of consciousness are part of how our brains work.

As human beings living modern lives, we also make decisions. The human brain is able to cope with decisions at various levels, ranging from deciding to sip a coffee to deciding to buy a house.

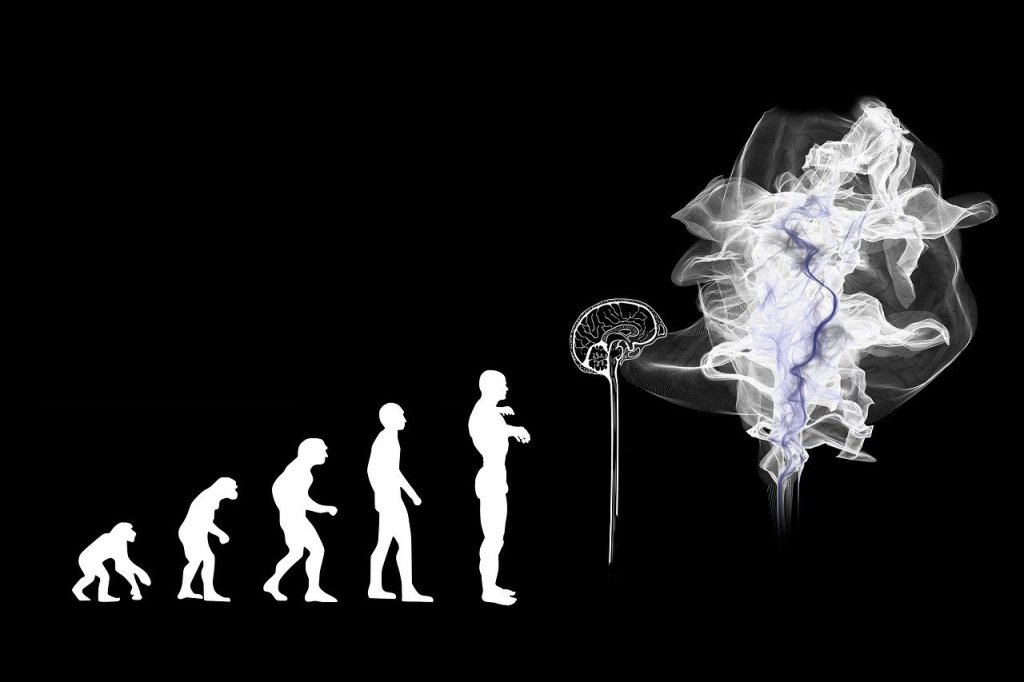

The first nervous systems were a simple, ladder-like network of fires through the body, linked to a simple tube – which we call the neural tube. There’s something similar in the bodies of modern-day planaria, or flatworms. It’s basic, but we know it works because they still survive today.

As animals became more complex, so did the structure of the nervous system. The front end of the neural tube began to become enlarged: it was the co-ordination centre which received information from the detectors that identified possible food, or light, or other information like vibrations, which implied that something large was nearby.

Those detectors eventually became the sense organs, and the enlarged front part of the neural tube became the brain. The rest of the tube, which passed along the body, became the spinal cord, and the cells that passed information to and from it became the somatic (bodily) nerves. But even though it became so much more elaborate, it was, and still is, a kind of tube. It just has many more knobby bits on the end than a flatworm has.

By the time of the dinosaurs, animals had become much more complex. That swelling at the front end of the neural tube had become a brain – not a very big one but one with different parts, which allowed it to co-ordinate the various bodily mechanisms needed to keep the animal alive, such as respiration, digestion and heartbeat. The brain also received information from the senses, which had become much more sophisticated, with their own separate organs and nerves and their own specialized parts of the brain. Movement and balance, too, had become vitally important functions, and a large part of the brain had developed to deal with these. And even a type of memory, although less complex than the memory we use, had begun to evolve.

Another set of animals had appeared during the time of the dinosaurs: the mammals. These had evolved another special part of their brains, which was able to control and regulate their body temperature. As a result, mammals could be active at night and avoid the reptile predators that depended on the sun for warmth and energy. Mammals evolved in other ways, too: they began to suckle their infants and nurture them after they were born, which allowed the young animals a safe time to learn about the physical world around them and to explore.

A small part of the mammals’ brain became specialized for adaptation and learning, so they were able to deal with unpredictable or changing environments. All this meant that when the world changed and the dinosaurs died out, the mammals were able to survive and take advantage of the ecological resources the dinosaurs were no longer using.

The mammalian brain, like that of other animals, adapted itself to the demands of its environment. Prey animals became highly sensitive to sensory information, developing acute reflexes enabling them to react quickly. Hunting animals developed in similar ways, as their survival required them to match the prey animals in order to catch them. Some animals were vegetarian, living only on plants; others were omnivores, exploiting whatever food sources they could find. And, most important of all, some of these lived socially, and shared their resources.

Source : Your Brain and You: A Simple Guide to Neuropsychology by Nicky Hayes

Goodreads : https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/39088936-your-brain-and-you

Read Next Article : https://thinkingbeyondscience.in/2025/03/25/how-the-brain-controls-movement-and-coordination/

Leave a comment