The first is that our brain has a tendency towards rose-tinted nostalgia. That’s why adults often describe their teenage years as ‘the best of their life’ (they almost definitely weren’t). They’re cherry-picking the aspects of teenage life they wish they had now (no mortgage/taxes/wrinkles) and forgetting everything else (hormones/homework/heartbreak).

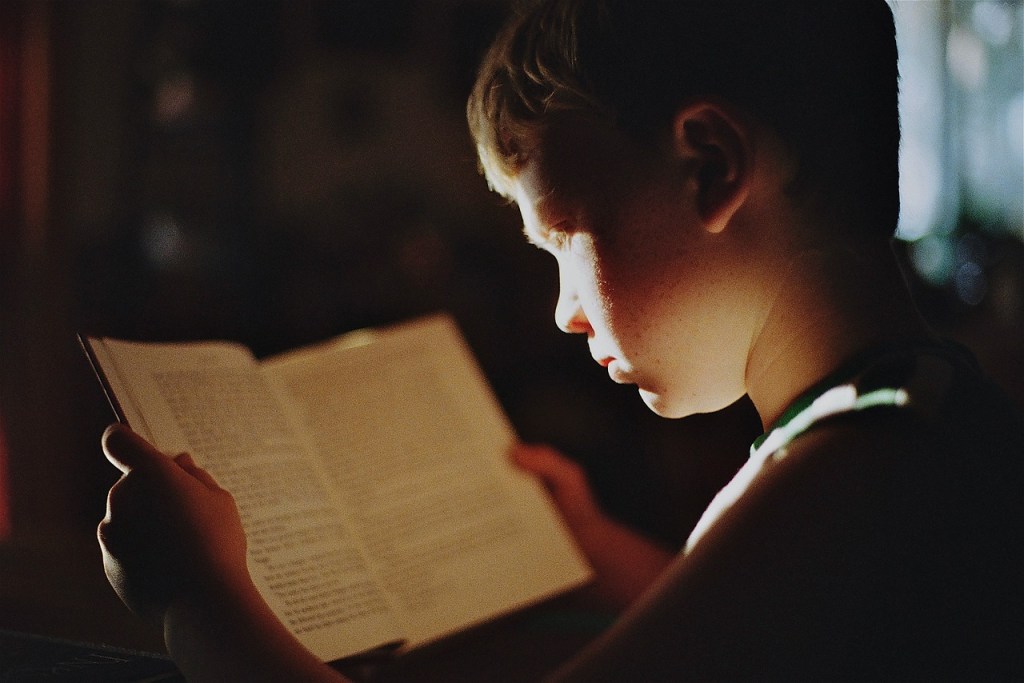

Where has the idea that academic learning and mental health are at odds with one another come from? I suspect the answer is, in part, the media. TV and radio shows are forever pitting stereotypical ‘trads’ (people who think education was better when pupils were seen and not heard, did their homework using a quill by candlelight and were thrashed with canes if they didn’t hand it in on time) and ‘progs’ (people who think schools should do away with reading altogether and pupils should instead go and sit under a tree to write a song about the beauty of a blade of grass, at the end of which everyone will get a medal for participating)* for entertainment value.

Everything is connected. Your physical fitness affects your mental health and the wellbeing of your mind impacts your ability to learn. Perhaps most excitingly, academic learning has been shown in numerous studies to make us happier and healthier.

One of the first parts of your limbic system to develop is the amygdala. The amygdala has one seemingly simple but fundamental job – to keep you alive. It is not concerned with context – it has no sense of the past or future and it doesn’t have any morality. As such, it is constantly scanning the area around you for evidence of a threat to your existence, or the opportunity for instant reward. If it perceives a threat it will initiate a strong and immediate response – dispatching chemicals to the rest of the body using your brain’s (vastly more efficient) version of DHL, known as neurotransmitters.

Fortunately, at around eight months old, we develop two septal nuclei – one for each hemisphere of the brain. These have the ability to inhibit the amygdala, so we aren’t just running around punching things all day. Have you ever seen those reins people attach to toddlers so they can walk within a limited radius of their care-giver and have a certain amount of freedom within safe parameters? The septal nuclei are the reins to your amygdala’s over-excitable infant.

There are other brain parts involved in the limbic system which I won’t detail here (including the hippocampi, which look like seahorses and are therefore quite fun), but it’s important to understand how it affects learning and wellbeing simultaneously.

The limbic system is responsible for secreting the vast majority (93%) of your total levels of a chemical called dopamine.

Dopamine’s job is to excite your brain cells, which makes it crucial for motivation, learning and concentration.

You’ve probably heard dopamine spoken about in relation to all kinds of addictions, from drugs to smart-phones. Whilst it’s true that anything addictive increases the amount of dopamine in our brains in a way that can cause us to become dysfunctional, the chemical also plays an important role in brain health. It’s getting the right balance which is key. Too much dopamine causes hyperactivity, whereas too little can lead to diseases of the nervous system (such as Parkinson’s).

Society deems we become adults at 18. I don’t know who decided that, but whoever it was didn’t know much about the human brain. Our brains don’t actually finish developing until we are around 24 years old.

That doesn’t mean, however, that we are children until then. In fact, the adolescent brain is completely unique and, in my humble opinion, totally brilliant. The bulk of my work is with teenagers and I love the way they’re smart enough to understand how the world works but open-minded enough to want it to change. Teenagers also think completely ‘outside of the box. If ‘the box’ was in, say, Paris, a teenager’s ideas generally come from somewhere near Pluto. This prevents my job from ever being boring.

Yet (in theory at least) a 20-year-old is smarter than a 10-year-old, so this pruning phase is meant to make our brain’s functioning more streamlined. Teenagers therefore have the combined curiosity of a child with some of the advanced cognitive skills that adults have.

‘In some ways, it’s strange that adolescence is when we are asked to sit exams, says Dr Bainbridge. ‘Between 16 and 18 you’re really just learning to use your new-found cognitive brilliance. Part of the reason the process feels so hard is because you’re still getting used to your new brain skills. If exams happened in your early 30s, for example, you’d be used to practicing self-analysis, which allows you to learn from mistakes and track where you have gone wrong.

Adolescence is also the time when we get our ‘third layer’ of awareness, which means that instead of focusing solely on our immediate surroundings, we are easily distracted. (Anyone who has ever tried to present to a class of teenagers and suddenly heard ‘SNOOOOOOOOW’ or ‘BEEEEEEEEEEEE!’ will attest to this.)

Exams are also a human invention. They don’t exist in nature – one doesn’t see a teenage giraffe having to write a paper detailing the specific significant dates in the history of giraffe-dom before it’s allowed to join the herd.

The human brain and body evolved during radically different times, when we lived a tribal existence that was more similar to that of other animals. Danger, in the context of tribal life, meant the prospect of being attacked by a predator or some other life-threatening event. Our physical responses to ‘danger’ signals from our brains (i.e. the chemical changes which create feelings of stress and anxiety) are therefore dramatic because, for a tribesperson, the situation usually was.

Source : Yes You Can: Ace Your Exams Without Losing Your Mind by Natasha Devon

Goodreads : https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/56058332-yes-you-can

Leave a comment