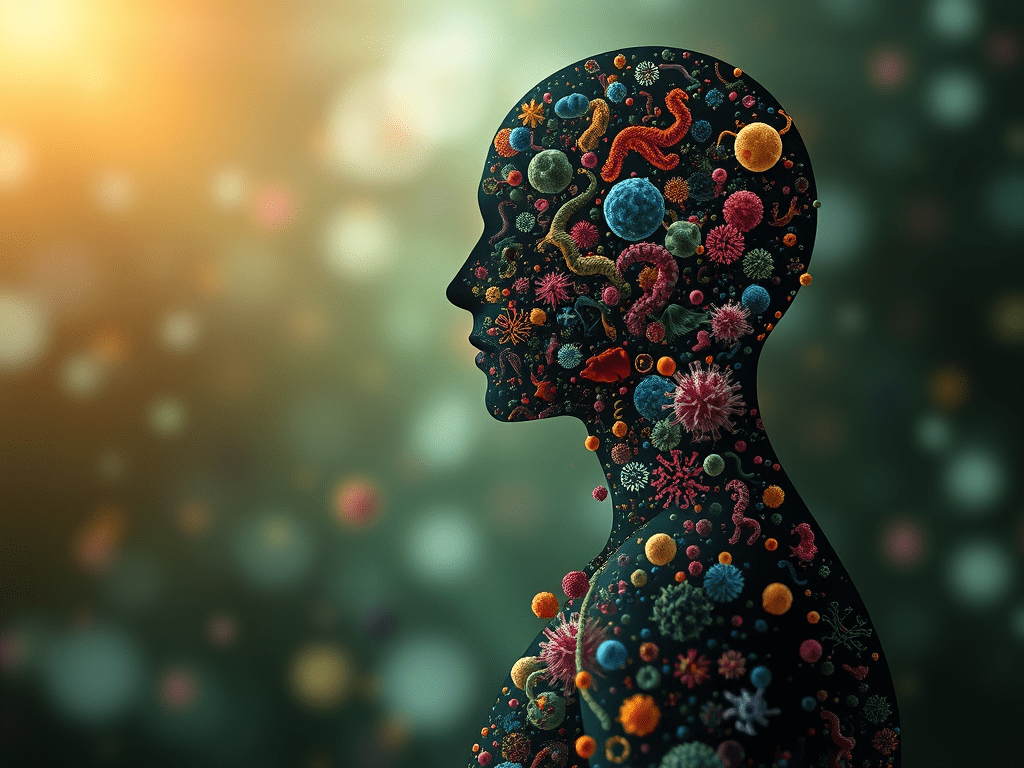

For every one of the cells that make up the vessel that you call your body, there are nine impostor cells hitching a ride. You are not just flesh and blood, muscle and bone, brain and skin, but also bacteria and fungi. You are more ‘them’ than you are ‘you’ Your gut alone hosts 100 trillion of them, like a coral reef growing on the rugged seabed that is your intestine. Around 4,000 different species carve out their own little niches, nestled among folds that give your 1.5-metres-long colon the surface area of a double bed. Over your lifetime, you will play host to bugs the equivalent weight of five African elephants.

Each of us is a superorganism; a collective of species, living side-by-side and cooperatively running the body that sustains us all. Our own cells, though far larger in volume and weight, are outnumbered ten to one by the cells of the microbes that live in and on us. These 100 trillion microbes – known as the microbiota – are mostly bacteria: microscopic beings made of just a single cell each. Alongside the bacteria are other microbes – viruses, fungi and archaea.

Viruses are so small and simple that they challenge our ideas of what even constitutes life. They depend entirely on the cells of other creatures to replicate themselves. The fungi that live on us are often yeasts; more complex than bacteria, but still small, single-celled organisms. The archaea are a group that appear to be similar to bacteria, but they are as different evolutionarily as bacteria are from plants or animals.

Together, the microbes living on the human body contain 4.4 million genes – this is the microbiome: the collective genomes of the microbiota. These genes collaborate in running our bodies alongside our 21,000 human genes. By that count, you are just half a percent human.

We now know that the human genome generates its complexity not only in the number of genes it contains, but also through the many combinations of proteins these genes are able to make. We, and other animals, are able to extract more functions from our genomes than they appear to encode at first glance. But the genes of our mi-robes add even more complexity to the mix, providing services to the human body that are more quickly evolved and more easily provided by these simple organisms.

Since life began, species have exploited one another, and microbes have proved themselves to be particularly efficient at making a living in the oddest of places. At their microscopic size, the body of another organism, particularly a macro-scale backboned creature like a human, represents not just a single niche, but an entire world of habi-tats, ecosystems and opportunities. As variable and dynamic as our spinning planet, the human body has a chemical climate that waxes and wanes with hormonal tides, and complex landscapes that shift with advancing age.

We have been co-evolving side-by-side with microbes since long before we were humans. Before our ancestors were mammals even.

Each animal body, from the tiniest fruit fly to the largest whale, is yet another world for microbes. Despite the negative billing many of them get as disease-causing germs, playing host to a population of these miniature life-forms can be extremely rewarding.

The more cells an organism is made of, the more microbes can live on it. Indeed, large animals such as cattle are well known for their bacterial hospitality. Cows eat grass, yet using their own genes they can extract very little nutrition from this fibrous diet. They would need specialist proteins, called enzymes, that can break down the tough molecules making the cell walls of the grass. Evolving the genes that make these enzymes could take millennia, as it relies on random mutations in the DNA code that can only happen with each passing generation of cows.

A quicker way to acquire the ability to get at the nutrients locked away in grass is to outsource the task to the specialists: microbes. The four chambers of the cow’s stomach house populations of plant-fibre-busting microbes numbering in their trillions, and the cud – a ball of solid plant fibre – travels back and forth between the mechanical grinding of the cow’s mouth and chemical breakdown by the enzymes produced by microbes living in the gut. Acquiring the genes to do this is quick and easy for microbes, as their generation times, and therefore opportunities for mutations and evolution, are often less than a day.

Our stomachs are small and simple, there just to mix the food up, throw in some enzymes for digestion, and add a bit of acid to kill unwelcome bugs. But travel on, through the small intes-tine, where food is broken down by yet more enzymes and absorbed into the blood through the carpet of finger-like projections that give it the surface area of a tennis court, and you reach a cul-de-sac, more of a tennis ball than a tennis court, that marks the beginning of the large intestine. This pouch-like patch, at the lower right corner of your torso, is called the caecum, and it is the heart of the human body’s microbial community.

Dangling from the caecum is an organ that has a reputation for being there simply to cause pain and infection: the appendix. Its full title – the vermiform appendix – refers to its worm-like appearance, but it could equally be compared to a maggot or a snake. Appendices vary in length from a diminutive 2 cm to a distinctly stringy 25 cm, and, rarely, a person may even have two of them, or not one at all. If popular opinion is to be believed, we would be better off without one at all, since for over one hundred years they have been said to have no function whatsoever.

The microbial second skin provides a double layer of protection to the body’s true interior, reinforcing the sanctity of the barrier formed by the skin cells. Invading bacteria with malicious intentions struggle to get a foothold in these closely guarded bodily border towns, and face an onslaught of chemical weapons when they try. Perhaps even more vulnerable to invasion are the soft tissues of the mouth, which must resist colonization by a flood of intruders smuggled on food and floating in the air.

Imagine, then, the climatic leap from the mouth to the nostrils The viscous pool of saliva on a rugged bedrock replaced by a hair forest of mucus and dust. The nostrils, as you might expect from their gatekeeper status at the entrance to the lungs, harbor a great range of bacterial groups, numbering around 900 species, including large colonies of Propionibacterium, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus and Moraxella.

Source : 10% Human: How Your Body’s Microbes Hold the Key to Health and Happiness by Alanna Collen

Goodreads : https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23644794-10-human

Leave a comment