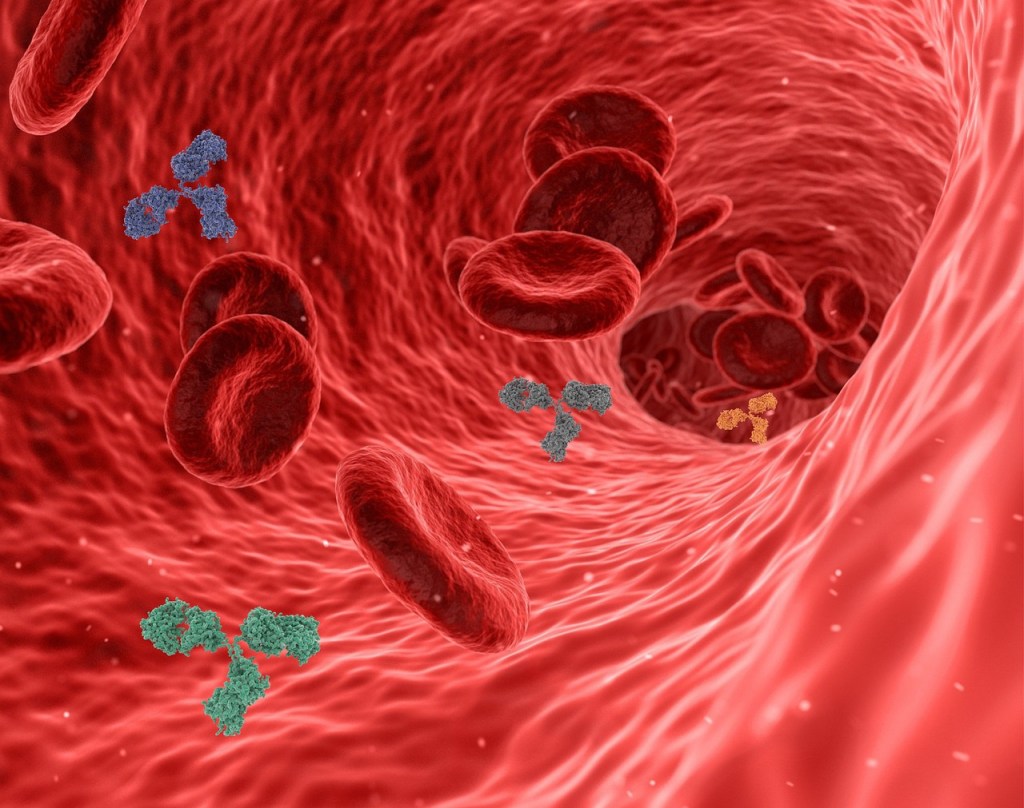

There are an estimated 3 billion B cells riding around in your bloodstream, each covered with sticky antibodies designed to match up with the antigens of diseases it will probably never meet, and which may not even exist.’ B cells spend most of their short lives floating around until they happen to get lucky and come across the corresponding unique antigen of a pathogen (such as an unfamiliar bacteria, virus, fungus, or parasite).

If the antigen they encounter happens to match up exactly with the unique antigen receptors of a particular B cell’s antibodies (which stud the B cell surface like cloves on a Christmas ham), that B cell snaps into action, producing clones of itself, identical daughter cells all born with the same “right” antibody.

In twelve hours, that B cell can make twenty thousand clones of itself, and the process continues for a week. Each new-made member of the B cell clone army also becomes a new factory, producing just that antibody against that disease cell.

Now it’s time to attack. The antibodies on the B cell surface fly out like sticky guided missiles at a rate of two thousand per second. Each of these antibody missiles has only one target: the unique non-self antigens on those foreign cells. They can see nothing else. The antibodies find and stick, accumulating on their target like burrs on a dog.

Not only does this trip up the disease cell, it also acts like a blinking neon sign that catches the attention of the wandering blob-like macrophages, drawing them toward a free foreign meal. The antibodies are sticky to the macrophages too. They bind them to their dinner. They also seem to stimulate the appetites of “nature’s little garbagemen” (a process known as opsonizing, from the German word that means “prepare for eating”). The foreign invader cell gets stuck, then gobbled.

It’s a fantastically elegant and sophisticated defense that ramps up a response to a new disease in about a week. When the threat is over, most of the B cell army dies off, but a small regiment sticks around, remembering what happened, ready to snap back into action if the threat shows up again. That’s called immunity.

B and T cells of the immune system look nearly identical under an optical microscope (part of the reason that, for most of the twentieth century, there was no such thing as a T cell). Just like B cells, T cells recognize a foreign antigen and ramp up a clone army to attack it. But T cells recognize and kill sick cells in a totally different manner.

B cells were known to originate in the bone marrow, travel the bloodstream for a while, and die. But some of these B-like cells seemed to take an extra side trip into a mysterious butterfly-shaped gland located just behind the sternum in humans, called the thy-mus; more of these cells were observed pouring back out of the thymus into the bloodstream. Even stranger, more came out than went in. Their numbers were sufficient to replenish the whole stock of B cells four times over, and yet, the overall number of lymphocytes in the body seemed to remain constant.

Viruses inject body cells with their virus DNA. Once that’s inside the cell, it’s too late for the B cell to stop it with antibodies. Eventually, that infected body cell will become a factory for more viruses, cranking out reinforcements for the disease. To prevent that and safeguard the body, that infected cell needs to be killed. If a virus does make it into a normal body cell and infects it, that cell changes. It starts expressing different proteins on its sur-face; it looks different, foreign. It’s up to the T cells to recognize those new foreign antigens of a self cell gone wrong and to kill that cell, up close and personal.

Recognizing a sick body cell, locking in on the telltale foreign antigen, and killing that sick cell are the T cell’s specialty. After the attackers are defeated, most of the immune clone army dies off, but a few remain and remember. If that attacker shows up again, it won’t take a week to clone up a new army and mount a defense. The body is ready. And that is immunity.

We all have about 300 billion T cells circulating through our bodies, each of them a lottery ticket randomly tuned to every possible antigen-recognizing combo. While that might sound like an enormous number, keep in mind that only those T cells that recognize the antigen fingerprint of an infected or a sick cell activate. And there’s no way for the immune system to predict what that antigen fingerprint might be. As a result, those 300 billion combinations need to account for and potentially match up with every possible antigen that nature might throw at us. ‘That means that in this antigen lottery, of those zoo billion possible combinations, at most only a few dozen T’ cells have the same winning ticket the exact right receptor capable of recognizing any one antigen, should it happen to show up.

Source : The Breakthrough: Immunotherapy and the Race to Cure Cancer by Charles Graeber

Goodreads : https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/39088907-the-breakthrough

Read Previous Article : https://thinkingbeyondscience.in/2025/02/16/the-role-of-b-and-t-cells-in-cancer-immunotherapy/

Read the Next Article in the Series :

Leave a comment