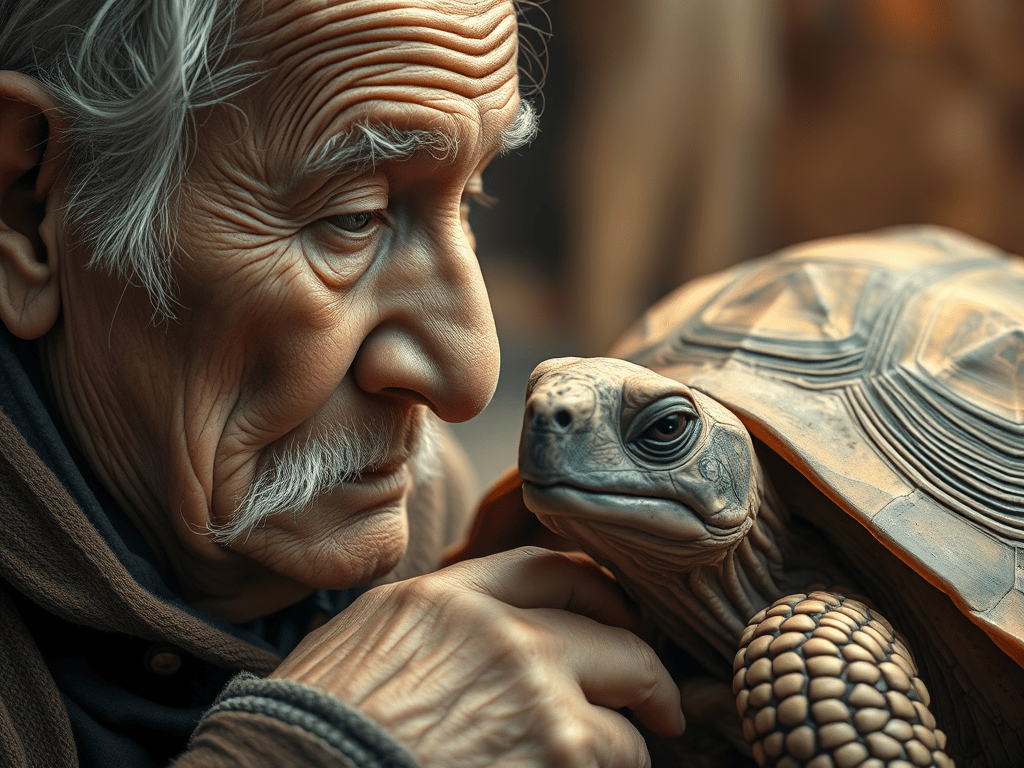

We humans are not so lucky. As we advance in years, we become wrinkled, frail and at increased risk of illness. Perhaps the most striking way to summarize our increasing frailty is to examine how our risk of death changes with time. Tortoises, being negligibly senescent, have a risk of death which is more or less constant with age: as adults, they have an approximately 1-2 percent chance of dying every year. We, by contrast, have a risk of death which doubles every eight years. This doesn’t start out so bad: aged 30, your odds of dying that year are less than 1 in 1,000. However, if you keep on doubling something it can start small but, eventually, get very large very quickly: at 65, your risk of death that year is 1 percent; at 80, 5 percent; and by 90, if you make it that far, your odds of not making your 91st birthday are a sobering one in six.

There is some evidence that this relationship flattens out after the age of 105 or so, meaning that these exceptionally long-lived people might have technically stopped aging – but, with odds of death around so per cent per year by then, they might wish it had flattened out slightly sooner.

We enjoy a relatively long period of fitness, perhaps five or six decades where our risk of death, disease and disability is fairly low, before a precipitous rise in old age. Aging happens to all of us and growing old brings experience and wisdom; to do so gracefully is something to aspire to. Since the dawn of life, ageing has been a natural part of being alive. Thus, the word ‘aging’ comes with a variety of connotations, not all of them negative. But, from a biological perspective, perhaps the best (and certainly the simplest) definition of aging is the exponential increase in death and suffering with time.

Understanding ageing could have enormous implications because it is by far the world’s leading cause of death and suffering. While that might sound counter-intuitive, looking at aging as a biological process makes the logic inescapable. As we age, our bodies accrue a familiar array of changes – from the superficial, like grey hair, wrinkles and elongating noses and ears, to the life-changing, like frailty, loss of memory and the risk of deadly diseases. The fundamental reason that our risk of death rises so swiftly is a rapid, synchronized increase in the odds of age-related disease. Even if you’re relaxed about death itself – we all have to go sometime, after all — then this risk of death is still a proxy for years of suffering at the hands of disability and disease which we would probably all rather avoid.

We humans are beset by a cocktail of cognitive biases which emphasize the here and now and minimize the distant future.

Most of us don’t save enough for our pensions and find it hard to stick to diets or exercise regimes. Human beings are also wired for optimism. We might picture ourselves grey-haired, retired, taking up new hobbies or playing with our grandchildren. We don’t picture being in hospital with an IV line and a bladder catheter. Research shows that we don’t deny the existence of cancer or heart attacks – just that few people believe it will happen to them. We also tend to extrapolate from previous experience. Thankfully, most of us don’t experience multiple simultaneous chronic diseases before we get old; when we picture our retirement, we don’t imagine being ill simply because we’ve not got much to go.

We now think that ageing isn’t a single process, but a collection of biological changes which make old organisms different from young ones. These phenomena impact every part of us – from genes and molecules to cells and whole systems inside our body — and go on to cause the aches and pains, worsening sight, wrinkles and diseases of the elderly. We are now at a stage where we can draw up a list of these changes and conceive treatments to slow or reverse each of them.

The ideas for treating ageing processes aren’t pie-in-the-sky theoretical biology — they are being tested in labs and hospitals around the world today. One such phenomenon is the accumulation of aged ‘senescent’ cells in our bodies.

Medicine for ageing itself could rejuvenate aged vessels and restore blood pressure to safe, youthful levels for the long term – and those same medicines would improve other aspects of our ageing physiology, too. The same biological processes which cause our blood vessels to stiffen are behind other problems, from arthritis to wrinkles; fixing root causes helps with many problems at once. Not only that, but truly controlling high blood pressure would go on to reduce the odds of further problems, from kidney disease to dementia, which are caused when blood pressure is high for prolonged periods. The changes which happen in our molecules, cells, organs and bodies as a whole as we age are why we are so susceptible to disability and disease – identify and learn to treat them, and the ill health of later life can be postponed.

In ancient Greece, Socrates and Epicurus were unworried by dying, believing that it would be like eternal dreamless sleep. Plato was similarly sanguine, but for different reasons: he believed that our immortal soul would go on existing even after our bodies had ceased to.

Aristotle was more concerned by death, and arguably the first philosopher to make a serious attempt to explain ageing scientifically in 350 BCE. His central thesis was that it was a process by which humans and animals dry out; as you will note from its absence in the rest of this book, sadly his theory hasn’t stood the test of time.

That structure is geared to the length and shape of a human life – just not necessarily the lives we live today, or will in the near future. We spend our first couple of decades in education, not thanks to some dispassionate analysis of the optimal duration of learning and development, but because we need to hurry on to the next stage and start work. Then, we try to earn money for 40 or 50 years, partly to provide for ourselves, partly to pay taxes and help the next generation through their early years and assist those already older than us, and partly to save for our own old age. Careers reflect this, with a steady rise through the ranks until we are in our forties or fifties, and a winding down there-after. The duration and nature of this period isn’t optimized either, but an accident of history, with ‘retirement age’ pegged to the age of onset of serious ill health during the first half of the twentieth century.

Source : Ageless: The New Science of Getting Older Without Getting Old by Andrew Steele

Goodreads : https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/52954648-ageless

Read Next Article : https://thinkingbeyondscience.in/2025/05/10/how-genes-influence-aging-and-reproductive-success/

Leave a reply to How Genes Influence Aging and Reproductive Success – Thinking Beyond Science Cancel reply